Behind the scenes of my solo show V E S S E L S at Willesden Gallery, London

“At times I think of human relationships as something soft like sand or water, and by pouring them into particular vessels we give them shape.”

Sheila, 2022. Photography by Amanda Rose.

It has now been exactly 6 months (to the day!) since my exhibition V E S S E L S opened at Willesden Gallery. Half a year seems like a good amount of time to reflect. I look back on it now with happiness and satisfaction at what I achieved - and great desire to build on ideas explored and connections made.

The title was inspired by the Sally Rooney quote above. I have long been influenced by literature (my degree was in Theatre Design) so the pairing between Rooney’s words and themes within my work came together quite naturally. I am interested in the idea of us being vessels carrying our exchanges and past.

V E S S E L S was my first solo gallery show and I’m so pleased it happened in Willesden which holds strong family connections. I wanted to write some thoughts down so they would always be here to come back to.

This blog post covers:

Brent and the Irish diaspora community

My family background

Archive research and issues uncovered

Irish women, motherhood and beyond

Ideas behind the paintings

Where I plan to take the work next

THE BEGINNING

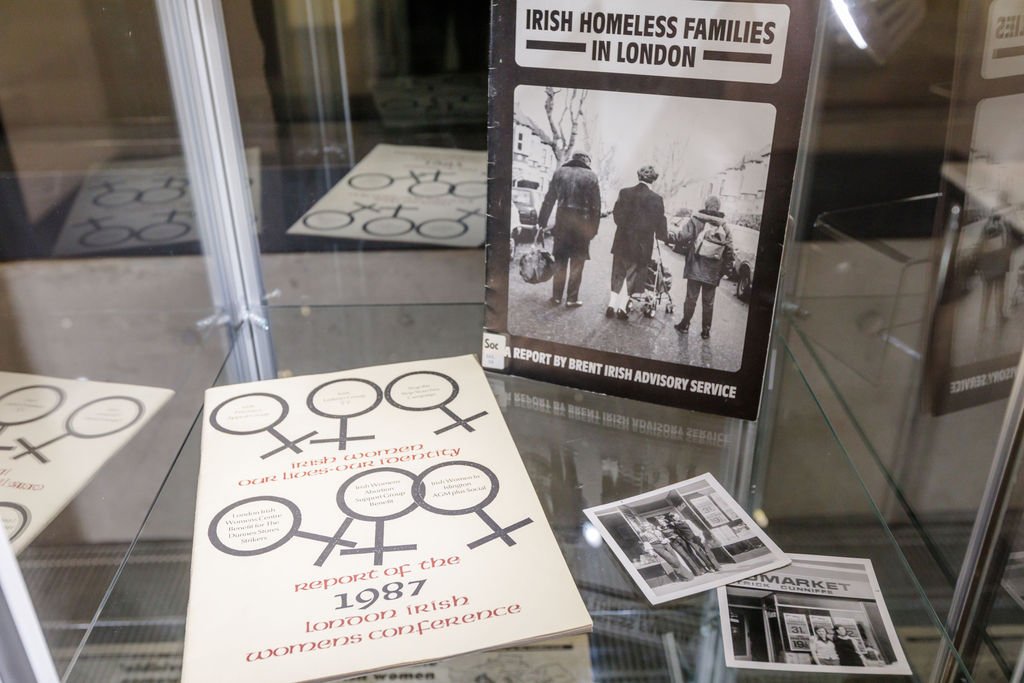

The exhibition began as a body of research into Irish migration to London (specifically Brent) from the 1940s onwards. I was born in Brent and took my first artist studio there in 2021 thanks to Second Floor Studios and Arts. My research took place at Brent Museum and Archives housed at Willesden Green Library, just upstairs from Willesden Gallery. My main areas of interest were Irish women, mental health and housing. I searched through boxes of newspaper clippings, pamphlets, information booklets and magazines all housed together under the ‘Irish’ section. The findings were both nostalgic and troubling.

Family photos - artists own. Photography by Amanda Rose.

My family forms part of the Irish diaspora, hence my interest in the subject. I am second generation Irish - my dad was born in Portlaoise and migrated to London when he was 21 and has lived here ever since. My mum was born in Willesden to Irish parents both from County Mayo - she grew up in North West London with her three brothers but went back home to Ireland every summer, a familiar custom amongst the diaspora community.

Diaspora in dictionary terms means ‘the dispersion or spread of any people from their original homeland’. It is common amongst the Irish community. My interests lie in the idea of being displaced as a psychological state - what it means to grow up in a country you do not originate from - where you place yourself and what you identify with. A longing for ‘home’ shaped my formative years - those left behind - present in every conversation, every interaction with extended family - a place I only experienced in short bursts or through watching Father Ted on the sofa. I feel at home in Brent.

Left to right: Thomas, Margaret and Christopher, 2022. Photography by Amanda Rose.

V E S S E L S exhibition view, Willesden Gallery. Photography by Amanda Rose.

A FRESH START

I became significantly more drawn to my heritage after giving birth to my son in 2018 - it seemed important to look back in order to move forward and make decisions true to myself. The ‘how’ and ‘why’ of traditions and values - things passed down to us without explanation - are a big area of interest and inspire much of my work. My upbringing was traditional Irish Catholic amidst North West London. I attended all Catholic schools and as a result most of my friends also had Irish roots.

My dad came to London in 1985 with his older brother to find work as a carpenter in the construction industry. London promised a new life - a fresh start. His experience was shaped by a strong need to earn money knowing there was nothing waiting for him back home - common amongst those from large families with little to no income.

My research tells me 20% of the homeless families who applied to the LB Brent for Housing in Feb 1988 were Irish, compared with an Irish population in Brent of 12% of the total population (Innis Housing report, 1987/88). Access to housing during this period was dependent on income and it was even harder for Irish women - often on low incomes. The traditional providers of temporary accommodation such as Irish ‘landladies’ were fewer and fewer so that many migrant workers were literally homeless although they may be employed.

Trip, 2022. Photography by Amanda Rose.

My painting above entitled ‘Trip’ came to represent the start of this body of work. I started it around the same time I began my research and it took many different forms. The feelings behind it are based on the impact of migration - on those that left and those that stayed behind. The abstract figure on top is beginning a journey or returning to a place of significance. Transparency is key - layers of emotions over time - the fluidity and ease of belonging contrasted with the complexity and desolation of displacement.

Artist Caroline Lovett viewing archival documents at the private view of V E S S E L S. Photography by Amanda Rose.

IRISH WOMEN

Irish-born women were most heavily involved in the lowest social classes, defined by occupation - they became nurses, domestic staff and bus conductors, or worked in light industry. As late as 1973, Irish women could be barred from work if they married on the grounds that they would probably have children and should be at home (Independent, March 1988). 57% of Irish-born women in London had no qualifications - a higher proportion than in any other group (The Invisible Irish Women April, 1988).

London Irish archival documents, Brent Museum and Archives. Photography by Amanda Rose.

Irish women have little historical continuity on which to base our identity. The surviving images of Irish women of the past are those which do not threaten the male notion of Irish identity. Pre-Christian images of women include goddesses, warriors and the celebration of female sexuality in sheela na gigs. Today the dominant images of Irish women are those of the housebound married mother and the fallen sinful woman - symbolising extremes of good and evil (Irish women our lives - our identity, 1987).

V E S S E L S exhibition view, Willesden Gallery. Photography by Amanda Rose.

V E S S E L S exhibition view, Willesden Gallery. Photography by Amanda Rose.

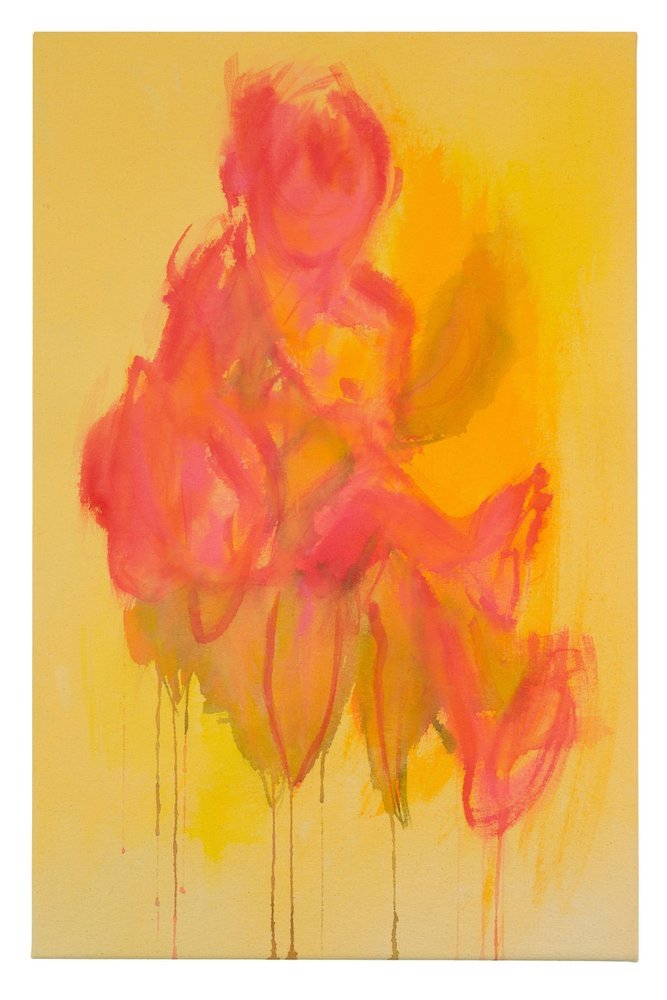

Amárach, 2022. Photography by Amanda Rose.

‘Amárach’ shown above depicts a mother and child, merged almost as one, fleshy and immediate. The work was made in relation to my own experience of being a mother juxtaposed with the views of the Catholic Church and the norm of having many children within my family. Ireland only allowed contraception for married women in 1979. The lack of control at caring for a helpless baby coupled with the lack of choice is completely overwhelming to think about. Amárach is Irish for tomorrow - used here as a bittersweet nod to a better day.

V E S S E L S private view, Willesden Gallery. Photography by Amanda Rose.

V E S S E L S private view, Willesden Gallery. Photography by Amanda Rose.

(Clockwise) Discreet, 2022; First love, 2022; Some kind of notion, 2022; Donkey Kong, 2022; Mary is my best friend, 2022; Keep on trucking, 2022. Photography by Amanda Rose.

“In Ireland you can have a home but no job, in England you can have a job but no home, nobody helps anyone else, nobody is making it clear to people about the realities of living in London.”

MENTAL HEALTH

The Brent Irish Mental Health group began in September 1985 after a public meeting on the issue concerning mental health among Irish people in Brent and the publication of a report on Mental Health and the Irish Community. The most vulnerable groups were single men and married women.

A high rate of homelessness and poor housing conditions, unemployment, low pay and poor working conditions, cultural problems and racism were contributory factors, as well as the Prevention of Terrorism Act 1974. Common stereotypes found in the archive included - ‘Is he mad or just Irish?’; ‘Boring old alcoholics and schizophrenics’.

Many mental health problems were repressed or unrecognised, or wrongly named - individuals left to internalise events and situations with disastrous consequences. The UK Capitalist environment offered no place to put these emotions. My perspective is both insider and out - not knowing the feeling of emigrating but growing up around those that did. My nan and her sister - both Irish-born living in Brent - would regularly sit and listen to Irish music together to ‘have a good cry’, an accepted way of emotions coming out.

Mother’s guilt, 2022. Photography by Amanda Rose.

‘Mother’s guilt’ shown above is an abstract depiction of a mother holding her child in her arms - you can see the child’s leg and foot on the right. The face is distorted to create a sense of unease - questioning the ‘perfect mother’ illusion - yet the colours are comforting and peaceful. There is a push and pull here - unresolved to me - a delicate area. The chain-like markings on the left are taken from a photograph of my mother in Ireland in her teens standing against a cart. The title hints at the overbearing and demanding nature of guilt both within Catholicism and motherhood.

Shilpa Bilimoria and I at V E S S E L S private view, Willesden Gallery. Photography by Amanda Rose.

IRISH IN BRITAIN AND WHERE TO NEXT?

During V E S S E L S, I collaborated on a drawing and reminiscence workshop with the Irish in Britain Cuimhne team which was a great way to hear more migrant community stories in the borough. Cuimhne (pronounced 'queevna') is the Irish word for memory. This workshop, as well as a previous talk I gave for Irish in Britain which you can watch here, cemented a solid bond with the charity. I am honoured to have been asked to be interviewed for Irish in Britain’s 50th anniversary heritage project. I will also be making exclusive drawings of Irish diaspora women for their touring exhibition November 2023.

In the studio, the theme of Irish women and Catholicism is prevalent. I had one nan who left Ireland in the early 50s and I grew up with, and one that stayed there, but sadly both are no longer here to ask about their experiences. I am interested in the difference of both their lives and subsequent families. I have already begun researching at the London Metropolitan University who house the largest collection of Irish in Britain material.

I wish to investigate Irish women of the diaspora further and explore where women sit within the world-wide commodification of Irishness manifested in theme bars and key-beer brands (Outsiders Inside, Bronwen Walter, 2000).

Thank you to curator Nadia Nervo, Joy Onyejiako, Brent Museum and Archives, Irish in Britain, Zibiah Loakthar, Carmel Murphy, Eithne Heffernan, Marianne Keating, Doug Devaney, Mal Rogers, David Hennessy, Bernard Canavan, Bob Matthews, Liane Lang, The ESOP, Turps Art School and my family and friends for their time, generosity and making this exhibition happen, and Amanda Rose for taking the wonderful photographs used in this post.

If you would like to receive updates from me and my upcoming exhibitions click here to join my mailing list.

PRESS

Second generation Irish woman paints the diaspora, The Irish Post, December 2022

New exhibition in Brent explores Irish diaspora stories, Irish World, December 2022